Fresh in my teens, I went to a tiny club in Berkeley, Ca., to see legendary heavy metal band Motörhead — a trio of hirsute dirtbags that rocked with the subtlety of a meat grinder.

I was a Motörhead newbie, green, callow, had only heard the raunch ’n’ rollers for the first time barely a year earlier. My deflowering was “Iron Fist,” Motörhead’s fifth record. It practically castrated me.

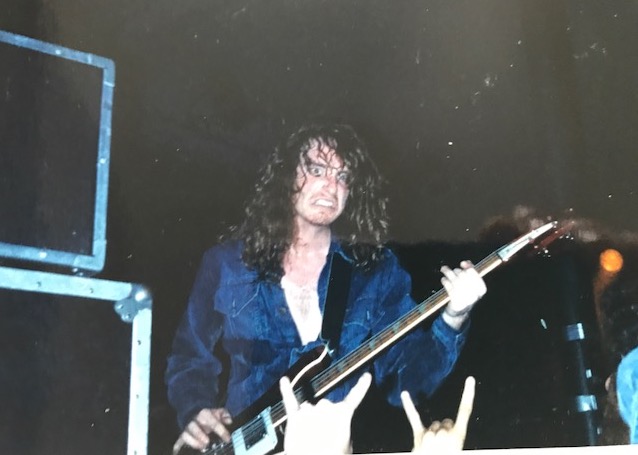

There I was, surely the youngest fan, along with my friends, in the closet-size club, a bit nervous amidst the cramped crowd of big, gnarly headbangers, scary-looking dudes with hippie hair and satanic glares. We kind of pressed ourselves against a back wall waiting for the show to start, innocents among animals.

And then something wild happened. Who did I see playing pinball on a rusty old machine but Motörhead bassist and lead singer Lemmy. The only person with him was a leggy blonde straight out of Playboy.

Now, Lemmy was a formidable, even fearsome presence, especially to a sheepish fanboy from the burbs. An icon of British metal, the towering singer seemed to have stepped out of central casting as a skull-crunching rocker, a road-worn biker from “Mad Max,” or a snaggletoothed pirate: leather jacket, black skin-tight jeans, bullet belt, cowboy boots, long greasy hair and scraggly muttonchops that hardly concealed two marble-size moles that many mistook for huge warts.

Lemmy drank and smoked fiendishly, and it would eventually kill him. His voice was a burnt-to-a-crisp croak. He didn’t play his bass, he mauled it, strumming it violently like a guitar, making the bulk of the distorted noise the band produced. One of their albums is titled “Everything Louder Than Everyone Else.” An understatement, and a promise.

(Incidentally, see the 2010 documentary, “Lemmy: 49% Motherfucker. 51% Son of a Bitch.”)

Excited and wide-eyed, I wondered what Lemmy was doing out there and not backstage committing all things illegal and squalid. Giddy dorks, my friends and I tried to figure what to do. Soon enough, I was the one who screwed up the courage to approach him.

So I went. And I, gulp, asked for his autograph.

He glanced down at me and, gruff, calm, unsmiling, said, “This is my time.” His voice was a gravel road of unknowable debauchery and spilled Jack Daniel’s. “See me after the show,” he added, a nice touch even if it was just a sop.

This is not why some rock stars suck. This is why some rock stars rule.

Chastened but exhilarated, I returned to my friends who asked what happened. Their faces read awe and disappointment. The girl out of Playboy snickered.

Nightclub shows like that, with three bands on the bill, and a late start time for the headliners, round midnight, meant we couldn’t really hang out afterward and hope Lemmy would be waiting with a Sharpie to sign an autograph. It was a wash and I knew it. Still, I had exchanged a few words with the man himself.

The show itself is a blur now, though the set list is archived online. (I cannot believe they didn’t play “Ace of Spades,” the band’s signature song.) But that encounter with Lemmy is branded in my brain. “This is my time.” I can still hear it in Lemmy’s smoke-charred voice, and it’s beautiful. Like watching a molten volcano, or surviving a shark attack.