In no particular order, the movies I’m excited about at the year’s half-way point …

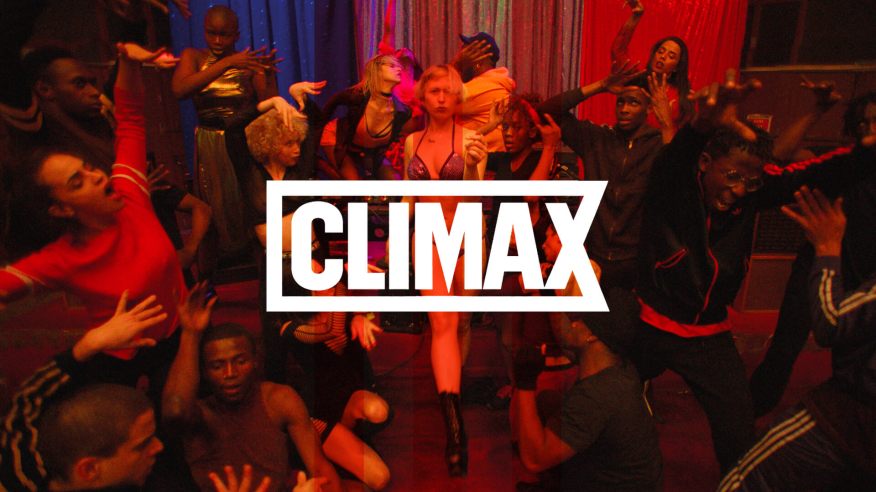

“Climax”

Puckishly sadistic, Gaspar Noé and Lars von Trier remain cinema’s great pessimists, glib nihilists and gleeful provocateurs. Look, without flinching, at Noé’s masterwork “Irréversible” or von Trier’s “Antichrist” and you’ll see my point. With the head-spinning, hallucinogenic swirl of body (and camera) movement that is “Climax,” Noé takes his visual and thematic tics past the edge of woozy chaos. When an extraordinarily talented dance troupe’s party is ruined by a bowl of LSD-spiked punch, hell uncorks with fury. What was a glorious pageant of writhing bodies becomes a descent into a violent nightmare of screeching, thrashing individuals trying to relocate reality. The camera rides a liquid wave of neon hues, racing and corkscrewing down halls and weaving through rooms. Frequently indulgent and meandering, with no real characters or story, just sensation and electro-shock, the film is pure immersion, a sustained climax. I didn’t say it was pleasant. But it is novel, and queerly riveting. And purely Noé. Watch the trailer HERE.

“The Last Black Man in San Francisco”

At once arty, elegiac, poetic and tough-minded, this is a tale, a beautiful reverie, that strikes on topics of race and class and gentrification with sparks and lyricism and primary-color Spike Lee sizzle. It’s something singular, and it slowly intoxicates with its emotional and sociological depths. Following Jimmie Fails (played by the actor of the same name — he’s as charismatic as a young Don Cheadle) as he presses to reclaim the giant Victorian home of his grandfather, the film is both a call to honoring blood bonds and a plaintive hymn to a troubled city. Joe Talbot directs (and co-writes) with soaring vision and intense feeling. The result is dire, daring, dreamy. Trailer HERE.

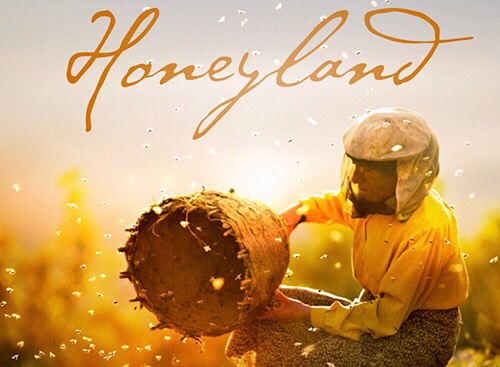

“Honeyland”

In this gorgeously observational documentary, weathered, middle-aged Hatidze lives in the rocky Macedonian mountains, where she cares for her ailing mother and tends to several beehives that produce honey for a tenuous livelihood. A large, rowdy family moves next door and decides to try beekeeping, but without expertise, they flail and almost comically get stung more than they harvest the sweet goo. Tensions arise between the neighbors, but this achingly humanistic look at an exotic if seriously impoverished way of life is mostly a portrait of Hatidze, a steely, lonely woman who has as much soul as those mountains can contain. The doc won a record three awards at Sundance 2019, including for its ravishing cinematography. Trailer HERE.

“The Mustang”

Breaking a horse is a bitch. Triple the challenge if it’s a rearing, snorting wild desert mustang. That’s what Roman (Matthias Schoenaerts) is tasked with as a violent criminal in a Nevada prison program in which convicts break mustangs for auction, preparing them for work in law enforcement. “We’re not training these horses for little kids’ birthdays and pony rides,” growls Bruce Dern’s crusty bossman, who knows both man and horse require an especially prickly strain of tough-love. If Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre’s feature debut falls into a formulaic groove — the apex of the depiction of trust-building between human and wild horse remains Carroll Ballard’s 1979 “The Black Stallion” — the film doesn’t flinch from gritty, violent twists. The dangerous dance between Roman and his horse Marcus retains tension, as the two captives, both scrappy and obstinate, circle each other in a face-off that could end in injury and defeat, or mutual respect and friendship. Roman’s frustration boils — “Just fucking listen to me!” he snaps. “I’m not going to hurt you! You hear me, you stupid animal!” — and it’s no surprise the horse is listening. Trailer HERE.

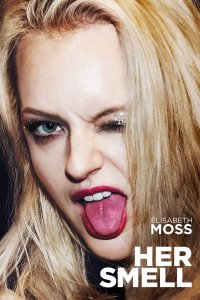

“Her Smell”

Elisabeth Moss’ performance in this shambolic punk-rock portrait is as athletically interior as it is exterior, spiked with physical fits and spasms like a lunatic child in a druggy tantrum. In my favorite performance of the year, Moss plays Becky, volatile front-woman of a female punk band she’s struggling to keep together between coke binges and flame-throwing hissy fits. The actress stirs up a cackling, hand-flinging cauldron of Courtney Love, Blanche DuBois, Charles Manson and Gena Rowlands in “A Woman Under the Influence.” It’s all raw-nerve, and Moss commits to her anti-heroine in a self-immolating blaze. She’s as shattering as this ballsy, surprisingly sensitive film by writer-director Alex Ross Perry. Trailer HERE.

“Booksmart”

Barreling forth with raunchy vigor and unbridled zest, this breakneck coming-of-age comedy, actress Olivia Wilde’s impressive directorial debut, screams fun. Almost literally: There’s a lot of screaming — in surprise, horror and explosive joy. An amplified spin on school-days greats — “Dazed and Confused,” John Hughes’ oeuvre and last year’s “Lady Bird” and “Eighth Grade” — “Booksmart” piles on twists with a sharp, knowing eye that zooms in on the timely and topical, from female power and LGBTQs, to bullying and the corrosive effects of cliques, and, duh, the liberating if daunting pull of sexual exploration. Starring a terrific Beanie Feldstein and Kaitlyn Dever as boundary-pushing besties, who learn, in a fleeting haze, that maybe bongs are as fun as books. Trailer HERE.

“Gloria Bell”

A glowing Julianne Moore — is there a more radiant actress? — assumes the title role in this sweet, ebullient, slightly melancholic snapshot of a middle-aged divorced woman seeking love and connection in modern Los Angeles. A touching remake of the 2013 Chilean film “Gloria,” by the writer-director of that movie, Sebastián Lelio, the movie follows its wise, free-spirited character onto her favorite place, the dance floor, where she finds romance with a nice guy (a fine, empathetic John Turturro) and all the attendant delights, complications and disappointments of love. No matter how sore things get, Gloria’s joie de vivre stays infectious. Trailer HERE.

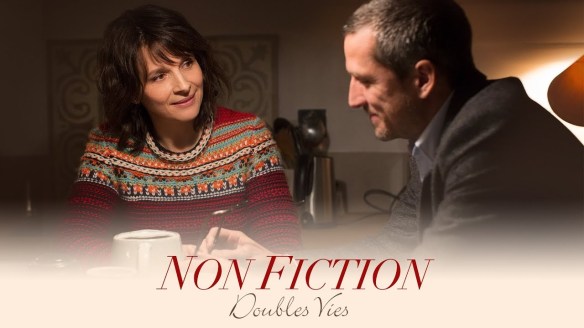

“Non-Fiction”

French writer-director Olivier Assayas‘ dramedy is a tireless, tonic gabfest that had me speed-reading the flurry of subtitles more than drinking in the warm faces and colors of the bustling scenes. That’s no complaint. The profusion of words — intelligent, eloquent, biting — brim with ideas, humor, pain and pathos, for an enveloping artful experience. You want to know the fork-tongued characters, led by an enchanting Juliette Binoche, because of the literary, arty cosmos in which these writers, editors and actors orbit. It’s heady and human: They’re just people, with all of our people-ly problems, and it’s more exciting than you think. Part tart publishing-world satire, part feast of infidelity, part anatomy of midlife crises, “Non-Fiction” is light on plot, more enmeshed in ideas about love and life, loyalty between friends and lovers, and, in a topical concession, a pointed conversation about new media vs. the printed word. It’s like a Gallic Woody Allen comedy, without the tootling clarinet and stammering, gesticulating neuroses. Trailer HERE.

“The Souvenir”

Not an easy film, Joanna Hogg‘s elusive, divisive relationship drama is boobytrapped with qualities that repel people from the arthouse. It’s glacial, elliptical, remote. It makes you work with loosely hanging scenes, a jagged structure and oblique characterizations. I broke a small sweat trying to solder the plot together, identify with the actors and figure out where Hogg was taking me. The entry point is young film student Julie, played with winsome diffidence by Honor Swinton Byrne. Julie’s lover Anthony (Tom Burke) is a heroin addict, a secret until it’s not, which inevitably snarls their relationship. The story is mostly scenes of the couple muddling through their unconventional, occasionally off-putting upper-middle-class affair. With drugs. And spats. And sex. And dinner parties. And the making of a student film. And an IRA bombing. Somehow, Hogg’s disparate elements crazily fall together. Trailer HERE.