During the post-holiday malaise, things poke and peck at my addled brain, fretting about the good, the bad, the grotesque …

Starting with the latter — the elaborate idiocy, the vomit-inducing venality of the so-called Donroe Doctrine, whose cutesy moniker makes me wonder: Who is he kidding with this crap? The perverted man-child is not kidding with, in his words, “my own morality,” which includes everything from ICE to Iran, a rogue’s gallery of revulsion. I pray that crippling tragedy looms in his wretched future. His crew of groveling lapdogs? Same.

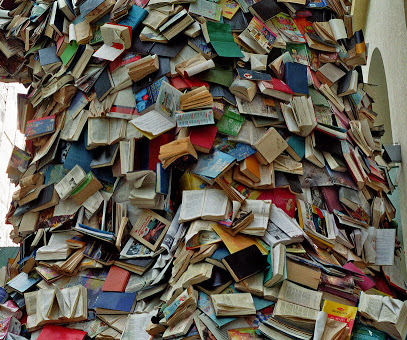

On the good side, I’ve cracked a newish book that’s been called by critics “a magnificent vision,” “transcendent,” “spectacular” and “not so much a novel as a marvel.” That would be Kiran Desai’s “The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny,” which is relatively slim for its daunting 700 pages. Yet what it lacks in girth it makes up in thudding weight. I could curl it and achieve Himalayan biceps.

I’m only on page 50 in this (let the publisher describe it) “story of two young people whose fates intersect and diverge across continents and years — an epic of love and family, India and America, tradition and modernity,” and I’m hooked.

It’s one of those chunky novels with character/family trees for a prologue, like “War and Peace” or “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” which can trigger the scram instinct in me. I don’t relish flipping back every twenty pages to recount who’s who.

But so far, very good. Desai conjures scenes and characters with creamy eloquence and imagery as supple as a Degas. The prose is wise and true, and funny, too. I only have 650 pages to go (sound of me lifting a cinder block).

Planning for two imminent journeys — Southern France in February and, implausibly, Nashville in March — continues unabated. It’s kind of a chore, but, like cooking or Lego building, it becomes a stimulating hobby, a minor challenge with low stakes.

I’m doing well so far in this First World folly, but the fine tuning feels endless. A Nashville restaurant I booked just emailed to say, sorry, your reservation is canceled because we are now “permanently closed.” The same happened with the Patsy Cline Museum (maybe these closings qualify for the “bad” in my opening paragraph), which a dear friend hinted is better than the popular Johnny Cash Museum. Call me “Crazy,” but I’m more interested in Cline than Cash. Bummer.

I voluntarily bailed on a street-art tour in Marseille, France, as I came to my senses that $194 is obscenely too much for a two and half-hour stroll amidst what’s essentially glorified graffiti. I don’t even know how I got myself tangled in that scam.

But I do that a lot. I plan trips with wide eyes and a growling stomach at first, and then, as the dates approach, I reel myself in and get sensible. Like, do I really want to do that whiskey distillery tour and tasting in Nashville? Well, yes. Yes, I do.

Denis Johnson’s “Train Dreams,” an exquisite novella I’ve read twice, once some years ago, once this winter, has been adapted for the small screen (Netflix) with mostly luminous results. Directed and co-scripted by Clint Bentley, the movie tells the story of a lumberjack razing towering forests in the Pacific Northwest to make way for the nation’s railroads. He marries. He has a child. Life intrudes.

Honoring the book’s ethereal touch, the movie aches to be a Terrence Malick epic: languid voice-overs, long traveling shots, fetishized natural beauty, breezes blowing through rustling trees, time-jumping episodes in place of linear plot.

It’s commanded by sylvan abundance and the honed, minimalistic performance by Joel Edgerton, whose eerie quietude is near-tragic if well-earned. Though cast in shadow, there is joy here — family, friends, sharp epiphanies. I was moved by the story’s rich poignancy and tender humanity. It’s as delicate as a dandelion.