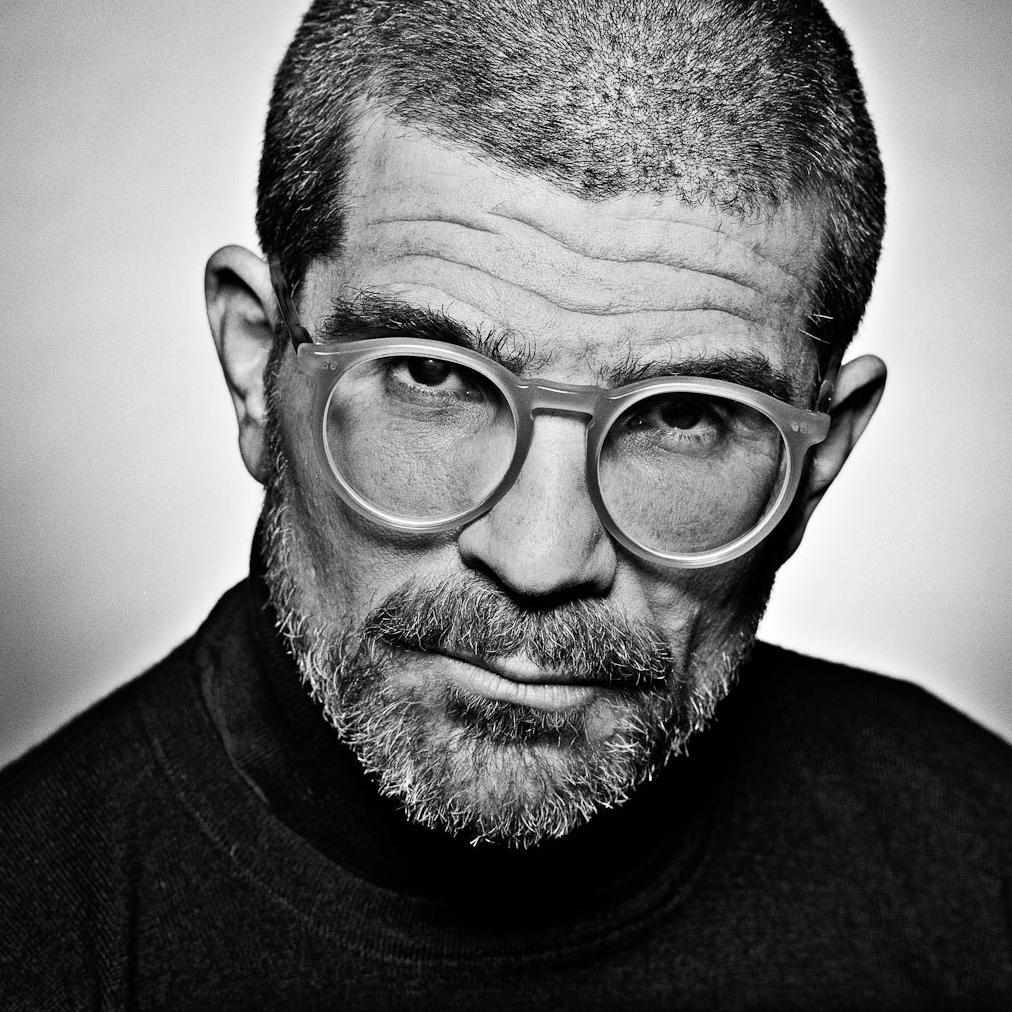

Indelible auteur, quiet crackpot, polite polymath, gentle genius, David Lynch, known mostly for his string of indescribable movies, died today at age 78. A lifelong, unrepentant chain-smoker, the artist/visionary announced he had emphysema last year, and defiantly declared he would not relinquish the pleasures of a good cigarette. And so …

In 2007, on the release of a new film and new book by Lynch, I interviewed him in Austin, Texas. This is how it went:

Watching a David Lynch movie, you might reasonably think its maker is living somewhere deep in the clouds. Speaking to Lynch only confirms this conceit, but in a charming, even sweet way.

Lynch, creator of some of the most willfully strange, and darkest, American cinema of the past 30 years, comes across as a crypto-naif — a polite, soft-spoken Midwestern gent wearing the mantle of a sophisticated abstract artist obsessed by dark, disturbing and unknowable things. It’s hard to reconcile the voice you hear on the phone — that of a pocket-protector accountant — with the father of “Eraserhead,” “Blue Velvet,” “Twin Peaks” and “Mulholland Drive.”

But cognitive dissonance is the currency of Lynch’s weirdly wonderful, inveterately arcane body of work. Take a look at his new film “Inland Empire.” The three-hour movie and my conversation with Lynch affirm the artist’s unbending faith in the abstract. Abstraction trumps the literal, he reasons, because it gives viewers a participatory role, allowing them to unriddle the conundrums he puts forth.

Lynch refuses to plumb the meaning of his work, asking audiences to approach the films with no prior baggage or knowledge. Which makes our job simpler, as it eases the obligation to write about what the sprawling “Inland Empire” is about.

Some facts: Lynch wrote “Inland Empire” as he went. He shot on digital video for the first time, making him an outspoken convert to the medium. He pieced a lot of it from previous projects, including 2002’s “Rabbits,” a nine-part, 50-minute short featuring actors wearing giant rabbit heads.

“Inland Empire” stars Laura Dern, who also co-produced, Jeremy Irons and Harry Dean Stanton, and features a handful of cameos. It is a difficult movie.

Lynch, 60, is on the road plumping the new film and his new book “Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness and Creativity.” In the slight and gnomic book, the Montana native shines a light on his 30-year devotion to transcendental meditation and its scuba-like potential to let practitioners dive many fathoms into consciousness and make otherwise unavailable discoveries in the mind’s darkest depths.

This, Lynch says, is where he finds his ideas. Lynch recently began the David Lynch Foundation for Consciousness-Based Education, which is aimed at teaching children transcendental meditation, a monument to his creative wellspring.

I recently spoke to Lynch.

The long, piecemeal process of making “Inland Empire” is becoming legend. Can you explain its unusual gestation period?

Well, it was a little bit unusual, but still the same, because it all starts with ideas. I got an idea that started when Laura Dern told me she was my new neighbor and her saying we have to do something together again. Thinking about that, things started rolling out and I started catching ideas and then I would write those ideas down and a scene appeared. Instead of keeping going and writing an entire script, I saw this as a stand-alone thing, not thinking in terms of a feature film at all. We got people together and shot that scene. Then I got an idea for another scene, unrelated to that first scene.

What was that first scene?

I don’t say, because I don’t want to putrefy the experience. Sometimes when people know a bunch of things they just start thinking about that. For me, I like to go into a film not knowing anything and letting it just happen. So I was shooting scene by scene, not thinking it was a feature until a bunch of ideas came that united the things that had come before. At that point I wrote much more and we shot in a more traditional way. Everything comes from ideas.

Watching “Inland Empire” is an often jarring experience and it does feel cobbled together from totally independent ideas. You’ll be in one scene or situation, then suddenly those darn rabbit-headed people pop up again. It’s discombobulating, but I assume you have a master plan holding the logic together.

Well, everything comes from ideas. And every idea starts talking to you and somehow things get together and the whole feels correct.

Why are you having ideas about people wearing giant rabbit heads?

Why does any idea come along? And why do we fall in love with them? Ideas that you fall in love with and think about and feel start speaking to you in a way that feels correct for the thing. If they’re abstract, you don’t always have a way of putting them into words that make the same feeling. That’s the beauty of cinema. Cinema can conjure things that can’t be said in words, except maybe by the great poets. They can stay abstractions. Many times in a film something pops up and then later the same thing pops up in a continuation. It’s the way stories unfold. It’s just the way it goes.

It sounds very organic put that way, but a critic might argue, “Yeah, you have a lot of ideas, but not all of them are thought through. You put the rabbit people in a satirical sitcom, but now what?”

I understand 100 percent, Chris. But if you just willy-nilly put things in, what is the point? The ideas start feeling correct even though you don’t know the whole story yet. A thing starts happening where the whole thing starts making sense, and it’s saying something for you, and it’s feeling correct. That’s how it goes with all the films. You may not know everything at the beginning, but you’re working on a script and it unfolds. It’s a huge gift, all these ideas holding together for you the filmmaker. And so you go like that, all pumped up with enthusiasm, feeling it and knowing it for yourself. Then you translate that through cinema and you’re rockin.’

Much of “Inland Empire” is easy to follow. Still, one might wonder what it’s about. Your official plot synopsis is just a single phrase: “A woman in trouble.”

That’s what it’s about. Obviously there’s more than that, and it’s there in the film. It’s not that I have fun not telling people things. The analogy I always say is that there are books where the author is long since dead and all that remains is the work. And you read it and the author isn’t around to ask questions of and you make sense of it yourself. To me, there’s a joy in that.

Do you mind that it sometimes seems like your ideas are vaulted in your head, inaccessible to everyone else?

No, because I think if it feels correct for one human being, chances are it can feel correct for others. When it’s abstract the correct feeling can come out in different interpretations. It’s like a long line of viewers stepping up to an abstract painting and each viewer getting a different feeling. If you wanted everybody to get the same thing you would make no room to dream. When things get abstract it’s open to whatever. Viewers know much more than they give themselves credit for. After a film, they go get a cup of coffee and talk to their friends, and before they know it they’re arguing over interpretations. All this stuff comes out, showing that they kind of internally knew (what was going on).

So you don’t mind asking a lot of your audience, particularly with the new film, which is nonlinear, opaque and a whopping three hours long? As one critic has written, it can leave an audience “baffled to the point of numbness.”

Some might feel that way, but if you talk to 10 people, all 10 won’t feel that way. It’s the viewer.

You’ve recently — and eagerly — joined the digital video revolution, and in Austin we have filmmaker Robert Rodriguez, who’s been evangelical about the medium’s virtues.

He’s a hero-champion. Digital video is a runaway train. Look at what people are taking still photos with now and you’ll see what’s happening with all of cinema. It’s digital and it’s here. There’s an opportunity for more and more people to let their voice out and realize their ideas. Freedom.

“Inland Empire” has a meta, film-within-a-film quality, echoing ideas of Hollywood, fame and moviemaking that you explored and critiqued in “Mulholland Drive.”

In a way the films are companion pieces.

That’s exactly how I felt. Can you elaborate?

No.

What are some of your obsessions? Lately you’ve gravitated to ideas about identity, split personas and parallel lives.

What I love are ideas, but not all ideas. How come certain people fall in love with certain ideas? It’s just the way they are. When you’re in love with an idea it’s such a beautiful thing. Then you know what you’re going to do and you can really enjoy the doing and translate that to a medium. It’s not like I say, “OK, I’m going to do something about an identity thing.” You get some ideas and later you realize, “Oh, it’s about that.”

In “Catching the Big Fish,” you are very generous sharing how you feel about transcendental meditation and how it’s transformed you. How has it affected your art?

One definition of human beings I’ve heard is we’re “humanoids reflecting the Being.” The Being is an ocean, unbounded, infinite, eternal, at the base of all matter and all mind. This ocean of pure consciousness, of bliss consciousness — creativity, intelligence, love, energy — is there and always has been there. It’s a human thing to learn how to contact this field and grow in it. And that means growing in creativity and energy.

The side effect of experiencing that deepest level is negative things start to recede, dissolve. That’s like stress, anger, fear, sorrow, depression all going. So beautiful for the artist or for any human being. It affects all avenues of life, and big understanding starts to come, appreciation for things and people. It’s so important to expand this consciousness and get yourself better equipped to catch ideas at a deeper level and understand them more.

As I put in the book, the artist doesn’t have to suffer to show suffering. Let the characters do the suffering. People say artists should suffer, they get ideas from suffering and all this. The more the artist is suffering, the less he or she can do. Real depression, real anger are a killer to creativity. So if you really want an edge, really want to do what you really believe in doing and have the power to have huge stressful situations come off your back like water off a duck’s back, just expand this bliss consciousness. The Being, this beautiful, beautiful, beautiful unified field — unity — expand that. Transcending is the only experience that utilizes the full brain.

Wow, whoa. You have your own coffee now, David Lynch Signature Cup. It seems a little gimmicky.

See, there’s the thing. There’s another expression: “The world is as you are.” There are lots of people who have their own coffee and there’s not a problem. We can do anything we want. So to put out a coffee that’s a good coffee to me is a beautiful, beautiful thing. I do love coffee, so roll it out.

Is it a special coffee; did you hand-pick it?

It tastes good to me. It’s the coffee I drink. It’s organic. It’s all fair trade. It’s a beautiful, beautiful thing.

***

Lynch on Lynch

In a game of free-association, I asked Lynch to offer a brief comment — or a single word — about some of his best-known works:

ERASERHEAD (1977): “My most spiritual film.”

THE ELEPHANT MAN (1980): “When I first heard the title an explosion went off in my brain, and I said, ‘That’s it.’ It was a true blessing to get that movie.”

DUNE (1984): “Heartache.”

BLUE VELVET (1986): “Hidden things.”

TWIN PEAKS (TV series, 1990) : “The mystery of the woods.”

WILD AT HEART (1990): “True love in Hell.”

THE STRAIGHT STORY (1999): “Forgiveness and brotherly love.”

MULHOLLAND DRIVE (2001): “A wondrous, hopeful dream of love.”