I’m never not reading a book or two. These are a few new titles I got my grubby paws on:

Mike Nichols’ 1966 film of Edward Albee’s corrosive play “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” remains a dish-rattling, drink-spilling, daggers-in-your-ears delight, all marital earthquakes and social Molotov cocktails. (Cocktails. Of course.) Booze is big in that cracked portrait of a long-wed couple on the rocks. (On the rocks. Of course.) And you get a contact high reading the riveting “Cocktails with George and Martha: Movies, Marriage, and the Making of ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’” by Philip Gefter, who capably captures the play’s serrated edges, dubious morality and verbal drive-bys, as well as the behind-the-scenes hoopla of making a controversial movie with a controversial couple, no less than Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor — Hollywood nitroglycerin. It’s a bracing blast of theater and cinema history.

“Headshot” is by a woman named Rita Bullwinkel. Let’s get that out of the way. (There, done.) This slim, tightly coiled novel is also a muscular debut, damp with the blood and sweat of a passel of female teenage boxers, zesty characters realized with pointillist panache. Time-leaping and fragmentary, the girls’ stories are told in intense vignettes for a scrappy scrapbook of pugilistic profiles that pounds with humanity and life. If not quite a K.O. — more tonal and rhythmic variety would shake things up — the book is a fleet-footed contender.

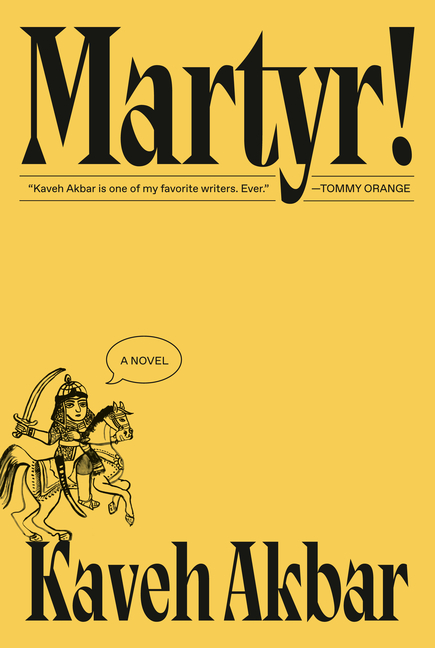

With irksomely precocious flair — at 35, he’s a wizardly wunderkind — poet Kaveh Akbar conjures worlds of art and ideas in his radiant fiction debut “Martyr!” Reeking agreeably of auto-fiction, this dense but delectably readable novel is about an Iranian-American poet scouring past and present, life, death and love with the insight of an artist and the squishy heart of the wounded. Gorgeous language propels you through its lush, gently philosophical thickets. And despite some muddled mysticism near the end — I’m allergic to spiritual allegory — “Martyr!” had me pleasantly reeling.

Lorrie Moore’s a personal favorite and her latest fiction is the knottily named “I Am Homeless If This is Not My Home.” Like all her books, tangy prose festoons the pages (a bite-size sample: “Fluorescent light rinsed the room.”). Yet the novel, with its arch surreal touches, rubbed me wrong. The narrative, centered on a man and his dying brother, is gawky, with sharp elbows and knobby knees. Plus, there’s heaps about chemo, cancer and croaking, and I’m not in a hospice mood. The novel just won the National Book Critics Circle award for fiction, so call me bonkers. In this rare instance, Moore is less.

Not for the feint of heart but perhaps for suckers for sentiment, the bleak memoir “Molly” — breathlessly written by Molly’s husband, Blake Butler, a noted novelist of thrillers — starts with her gunshot suicide and continues with another bang, the crack of bared emotion and tell-all candor. This is the story of Butler and Molly Brodak’s three-year marriage, a melding of art and nature and words and, in her case, bouts of inconsolable darkness. Brodak, a published poet and author who said “I simply wasn’t good enough,” killed herself three weeks before her 40th birthday, in 2020. “Molly” is so much about her and her devastating secrets, yet equally about Butler’s clawing to the other side of grief through deep (and verbose) psychic excavation. He includes Molly’s suicide note (“I don’t love people. I don’t want to be a person”), along with the frantic blow-by-blow action of finding her body in a favorite field of theirs. These passages are tough-going, not only for the forensic particulars, but for Butler’s writerly histrionics as well; he pants on the page. A cult sensation, tugging readers to and fro like emotional taffy and kicking critics into superlative overdrive, “Molly” is a divisive read, by turns lovely, wincing and overheated. It is the first book I’ve read that opens with the phone number for the national suicide hotline.