Who likes poetry? I mean, who sincerely enjoys and delights in the art’s nose-crinkling inaccessibility, willful allusiveness and opaque flights of fancy? Who, really, likes to be flummoxed?

I do. Not much. But a little.

With a philistinian gulp, I admit that I prefer my poetry streamlined, simple, more aerodynamic than pyrotechnic. “Prose poetry” — the wondrous fictions of Nabokov, Marquez, Marilynne Robinson, Cormac McCarthy, to name a few — is what I really savor, alongside the vaulting, tongue-tangling verse of Shakespeare’s plays. (I haven’t worked hard enough to appreciate the Bard’s beloved Sonnets. I know, I know. Poetry, see, so often requires toil. I tire easily.)

Recently reviewing the great Ben Lerner’s book-length essay “The Hatred of Poetry,” The New York Times remarked: “A lot of people seem to hate poetry, which is arguably neck-and-neck with mime as the most animus-attracting of art forms. Loathing rains down on poetry, from people who have never read a page of it as well as from people who have devoted their lives to reading and writing it.”

I‘m loving the Times.

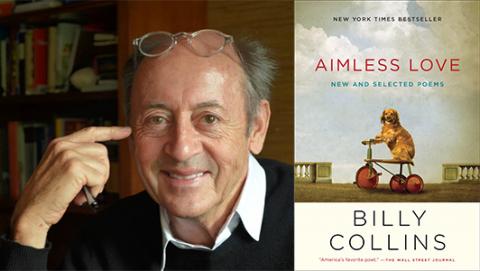

Now, here’s what feels like a blushing confession, a bald admission that I am, at long last, a quasi-poetryphobe. And that is: My favorite poet is Billy Collins. Elfin in aspect, with a humble mien and dazzling intelligence, Collins might be the most popular poet in America. His publishing deals are staggering. He enjoyed two stints as U.S. Poet Laureate. His readings are thronged. He’s like the Tom Hanks of poetry.

He also might be one of America’s most loathed poets, caught in that love-hate swirl of backlash — or simple lash. He’s deplored by many readers, critics and fellow poets, dismissed as easy, anodyne and frivolous, appealing to the lowest-common denominator, the beach-read slugs.

As The Buffalo News said: “To his critics, Collins is a ‘major minor’ poet at best whose work is formulaic, if not predictable, and whose relentless efforts to charm the reader assume that the only way a poem can work is on the demotic level, which is to say, as colloquial speech.”

An online wag cracked: “Billy Collins is to good poetry what Kenny G is to Charlie Parker; what sunset paintings at the mall are to Jackson Pollock.”

Or, jeez, perhaps Collins is the Thomas Kinkade of poets.

Then again, no.

Collins’ gently cascading language is deceptively dismissible. It doesn’t boogie; it waltzes and sways. The poems are indeed colloquial, plain-spoken, but the artist braids his mini-narratives just so, to surprising and droll effect. Explosions are rare. He ferrets out little truths in life’s nooks, casting a soft, never-blinding light on them, hoisting them as shiny epiphanies that make you nod in gratitude.

Almost consistently funny, his poems are also often dark, shot through with self-deprecation and doubt about the whole racket of writing. It’s charmingly self-referential, even a bit neurotic.

Collins is the master of “witty poems that welcome readers with humor but often slip into quirky, tender or profound observation on the everyday,” That’s the Poetry Foundation, which also cites no less than John Updike (speaking of an exemplary prose poet), who praised Collins’ “lovely poems” as “limpid, gently and consistently startling, more serious than they seem, they describe all the worlds that are and were and some others besides.”

Read for yourself here.

One of Collins’ poems, “The Country,” which opens the fine collection “Nine Horses,” hooked me early on, made me follow him all the way:

I wondered about you

when you told me never to leave

a box of wooden, strike-anywhere matches

lying around the house because the mice

might get into them and start a fire.

But your face was absolutely straight

when you twisted the lid down on the round tin

where the matches, you said, are always stowed.

Who could sleep that night?

Who could whisk away the thought

of the one unlikely mouse

padding along a cold water pipe

behind the floral wallpaper

gripping a single wooden match

between the needles of his teeth?

Who could not see him rounding a corner,

the blue tip scratching against a rough-hewn beam,

the sudden flare, and the creature

for one bright, shining moment

suddenly thrust ahead of his time —

now a fire-starter, now a torchbearer

in a forgotten ritual, little brown druid

illuminating some ancient night.

Who could fail to notice,

lit up in the blazing insulation,

the tiny looks of wonderment on the faces

of his fellow mice, onetime inhabitants

of what once was your house in the country?

That poem cracks me up every time. It’s funny yet concerned, a little nerdy. (You can watch an animated video of the poem here.)

Thing is, Collins wants poetry to be easy and lucid and fun and moving. He’s curated two volumes of such work, “Poetry 180: A Turning Back to Poetry,” featuring poems by, among others, Catherine Bowman, Philip Levine, William Matthews, Paul Muldoon, Mary Jo Salter and Pulitzer Prize-winner Stephen Dunn, my second favorite poet, who also traffics in prosey stylings that illuminate life with wry melancholy. (Check him out, especially, I think, “A Postmortem Guide,” which I’d like read at my own ashes scattering. Classic stanza: I learned to live without hope/as well as I could, almost happily,/in the despoiled and radiant now.)

It doesn’t matter that Collins is no Larkin, Wordsworth, Heaney, Dickinson or Keats. Hell, maybe he is. I don’t know. But like the best art, his quirky poems are nourishing. They stimulate and tickle. They please me. I think that’s enough.