Been enthralled rewatching the eight-part docuseries “Simon Schama’s Power of Art,” keeping winter’s brrr at bay with deep insights and gobsmacking grandeur. The 2006 BBC show, now streaming, profiles an octet of artistic titans hosted by the smartest guy in the room, scholar and scamp Simon Schama, known for a heap of cultured feats, including “Citizens,” the landmark history of the French Revolution.

With theatrical kick and piercing opinions, Schama surveys these pigment-stained characters in one-hour slices: Caravaggio (blood, beauty and butchery); Bernini (boggling, blissed-out sculpture); Rembrandt (peerless Dutch portraits — “Mr. Clever Clogs,” Schama cracks); David (the divisive “Death of Marat”); Turner (violent squalls of blinding light); Van Gogh (dazzling swirl-scapes, with an ear to the ground); Picasso (Cubism: Braque ’n’ roll); and Rothko (pulsing rectangles of preternatural color).

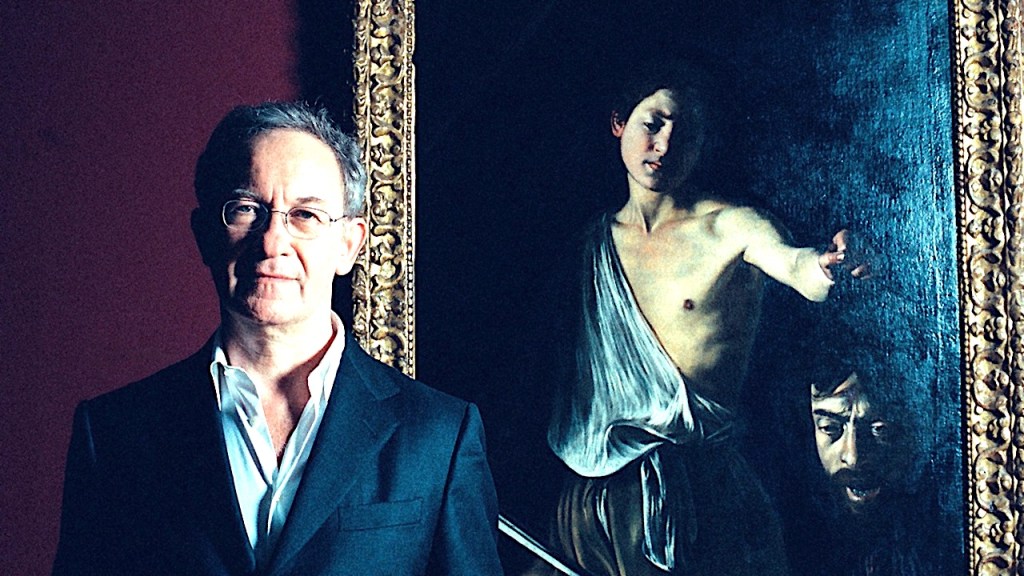

Tweedy but cool, shirt buttoned low, Schama is a delight. He deploys effortless erudition with an impish glint in his eye, a calibrated smirk and a gift for eloquent, giggle-making irony — he’s brainy and funny. But he’s also dead serious, reverent, about his heroes and their eternal masterworks. Art, he seems to say, is no joke. Except when it is.

As one observer says, “Schama is not neutral; he argues, provokes, and interprets boldly,” adding that the series “helped shift popular art docs away from polite scholarship toward emotion, conflict, and stakes.”

It’s how he peels back the works’ essence and the artists’ humanism that stands out. For example, he not only declares but demonstrates how Van Gogh “created modern art” amid a maelstrom of mortal mental distress. (That chapter is understandably the most heartbreaking.)

If you like transcendent art — “Slave Ship”! “Starry Night”! “Guernica”! — cinematic reenactments with fine actors in real locations, and the sly, conspiratorial air of a charismatic host, the series is a feast. More than edifying, it’s electrifying.

Just listen to this guy: “Great art has dreadful manners,” says Schama, who writes every episode. “The greatest paintings grab you in a headlock, rough up your composure, and then proceed in short order to rearrange your reality.”

Right about there, my knees buckle.

I’ve been blabbing here about going to Marseille in early February. A picturesque coastal city, the second largest in France, it’s famed for a gritty, hip, multicultural vibe, a fabulous port and craggy shorelines kissed by Listerine-blue Mediterranean waters.

Marseille is also famous for its motley cuisine, from French and Moroccan to pizza and West African. But above all it’s known for the iconic, somewhat extravagant seafood stew, bouillabaisse — rich, aromatic and typically made with various Mediterranean fish.

The recipe generally goes like this, and here I’m cribbing:

A traditional bouillabaisse has two parts:

- The broth – saffron-gold, flavored with fennel, garlic, tomato, orange zest, olive oil, and Provençal herbs.

- The fish – several firm, rock-dwelling fish from the Mediterranean, added in stages so each cooks properly.

Now, many hot-shot chefs mess with the recipe, adding shrimp, lobster, mussels and other mollusks, god forbid. This bouillabaisse virgin — never had it! — is allergic to shrimp and lobster (an adult-onset allergy; I love shrimp), so I fretted about where I would get a purely traditional fish stew in Marseille.

All the guidebooks and websites point to one restaurant, Chez Fonfon, which has been serving bouillabaisse for 74 years using scorpion fish, red mullet, eel and other fishies in its recipe. “We offer to prepare the fish in front of you or already prepared for immediate enjoyment,” says the Fonfon site. I’ll take the show, please.

Then, as is my wont, I over-thunk the meal. What if they also add shrimp or lobster? I’d just have to see. Or not. Yesterday I emailed Chez Fonfon and asked the question. A few hours later they responded.

“Our bouillabaisse is prepared in the traditional way, using only rock fish and vegetables. It does not contain any crustaceans such as shrimp or lobster.”

Jackpot. Now I can sleep at night and dream of rock fish swimming in my bowl, sans crustaceans stinking up the joint, toxic creatures that would make my throat swell, my breathing sputter, likely ending in my death, face-down in my very first, and last, bouillabaisse. Merde!