As a kid, from ages seven to 17, I had subscriptions to sheaves of magazines I eagerly awaited to hit my mailbox — Dynamite, Ranger Rick, Hit Parade, Modern Drummer, BMX Action, Omni, Heavy Metal, Movie Monsters and more.

Each title represented a discrete passion — showbiz, animals, rock, drums, science, bikes — and the glossy journals were bibles of my interests. I read them rapt, lapping up interviews, gossip, photos, front-of-the-book ephemera, often scissoring them to bits for bedroom wallpaper and school-locker decor. (Try that with an online subscription.)

At about 17, I started reading the local newspaper, the San Francisco Chronicle, with a new seriousness that went beyond comics “Bloom County” and “The Far Side.” I loved the stylish writing, current events, cranky columnists and clever critics. It was a daily feast, and each week I’d spend up to three hours poring over the overstuffed Sunday edition, an inky ritual I savored.

I also read lots of books — “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” to freak show biographies; “Slaughterhouse-Five” to Jim Morrison’s (dreadful) poetry — but that’s a given. When I was eight I read the fat paperback of Peter Benchley’s “Jaws,” and I’m still proud of it.

But is it normal, for a boy at least, to spend so much time with the written word, reading? Shouldn’t he be outside, say, throwing balls, or blowing things up?

While I hated most sports — except soccer, skiing and BMX — I was your average knee-scraping, war-playing, B.B.-gun-shooting, lizard-catching, fire-setting, doorbell-ditching, girl-crazy, grungy little scamp.

Still, I adored words and what they imparted — ideas, information, whole worlds. I used to wade through our World Book encyclopedias and ginormous Mirriam-Webster dictionary just for fun. My best friend Gene and I wrote little books about devils, murder and other unspeakable mischiefs. We had a thing for horror.

But did all that bibliophilia and word-love mean I was a giant wuss?

This week teacher and novelist Joanne Harris — bestselling author of “Chocolat” — said that reading is far more rare in boys than girls, for rather macho reasons:

“When I was teaching boys particularly, I found that not only boys did not read as much as girls but they were put under much more pressure by parents, largely fathers, to do something else as if reading was girly,” she said via LitHub. Boys, apparently, “ought to be out playing rugby and doing healthy boy things.”

And I reply: Can’t boys do both — reading and “healthy boy things” — like I did (and what’s a healthy boy thing, anyway)?

Forbes reports that boys are way behind girls in reading comprehension and writing skills, because “reading and writing are stereotypically feminine endeavors, and boys tend to avoid anything that’s remotely feminine. In other words, it’s just not cool to read, because reading is for girls.”

This is clumsy and reductive (and offensive) reasoning, more fitting for the playground than a hard, rational study. Reading is for girls? You don’t say.

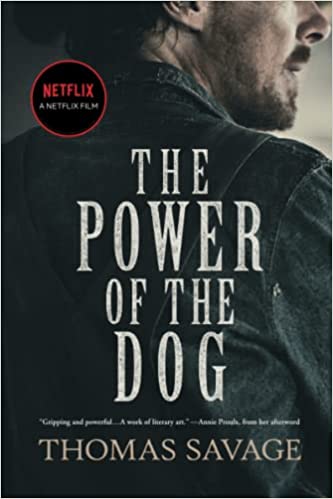

What then to make of all the wildly famous male writers overpopulating the literary canon who have (unjustly) eclipsed their female counterparts? Call Hemingway or Mailer a wuss and see where that lands you.

I don’t doubt that girls read more than boys; I’ve seen it borne out. If it’s because boys are discouraged and intellectualism is deemed unmanly, then we have a real societal problem. I don’t have the answers — just my umbrage — but if you have any thoughts, please comment.

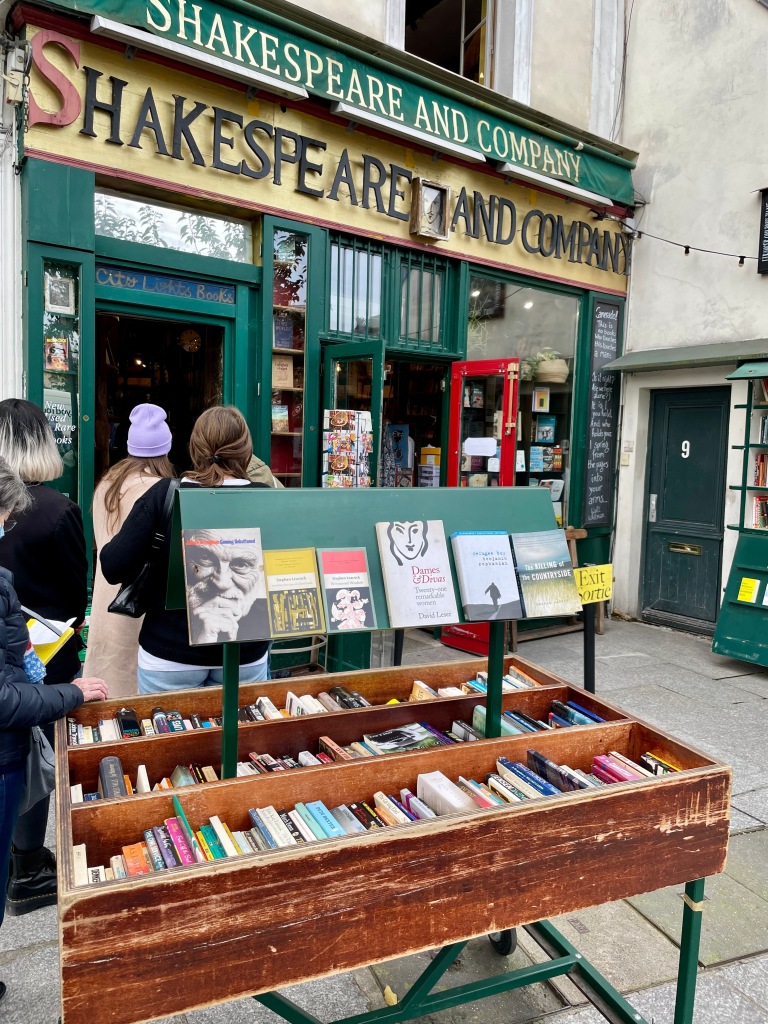

I know many bibliophobes, people, almost all male, who would never think of strolling the living, fragrant stacks of a bookstore, or simply pick up a book for that matter. To me, they’re the wussies, un-evolved, willfully ignorant, with the vocabulary of third graders and the critical thinking skills of a hubcap. I don’t trust adults who don’t read. Philistinism is a cultural crime.

World travel has largely usurped my juvenile need to start fires and catch lizards, but I still read at a mad clip and write as much as I can. Call me a sissy. I’m having a ball.