1. I don’t do dragons. I think they’re silly. For all their fiery tantrums and wing-flapping fury, I can’t take them seriously. Humans ride on their scaly backs like they’re horsies and fly through the sky. I crack up whenever I see that.

So needless to say I’m not watching HBO’s “House of the Dragon” or Amazon’s “The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power,” big ticket fantasy orgies that by turns bore and baffle me. I don’t even know if “Rings of Power” features dragons — halitosis-impaired Smaug looms large in Tolkien’s Hobbit-verse — but I also don’t do elves or wizards, Orcs or even swords, so I’m pretty much locked out of those good times.

But I’m not a complete dragon-phobe. My favorite dragon movie is easily “Reign of Fire,” starring Christian Bale and a bald Matthew McConaughey as gnarly post-apocalyptic dragon slayers. If you haven’t seen it, do. It’s a blast. McConaughey chews on a big fat cigar throughout. There’s fire and volcanic sludge and dragons all over the place. It’s also pretty grim. And nobody rides a dragon.

2. My brother and his wife just got back from Madrid — precisely where I am headed 20 days from now. No conspiracies, no subtext, we just happened to agree that Spain’s capital is the place to be this month, this year, right now.

What’s great is that I sent the lovely couple on a sort of expedition to scope the city, suss out all the hot tapas bars and cocktail bars, the most electric neighborhoods, what sights to see and what to skip.

And they delivered resoundingly, finding me a better hotel in a livelier area, several hip restaurants and bars, a shrine to Goya, and a slew of invaluable practicalities. Teamwork! High five! Madrid is famous for its blaring all-night carousing. You still hear people banging bongos in the street at five in the morning. I land on Halloween. I hope it’s batshit.

3. The ongoing saga of my misadventures in sneaker shopping — the subject of a prior post — is finally winding down. I spent the summer agonizing over what shoes to get to replace my moldered, moth-eaten collection of casual kicks.

Halt. Mere minutes ago, after I wrote that paragraph, I ordered the final pair of sneakers I will order this year. (I hope.) Just as I was getting comfortable with some slick new Cole Haans, I stumbled on a pair of rare New Balance sneaks that I fell for instantly. Now what? I put the Cole Haans back in their box (for the moment) and clicked “Place My Order” on the New Balance.

Which means I’ve now, since July, bought seven pairs of sneakers, an unholy sum that has me and my Visa doing barfy loop-the-loops. What else: I got another pair of New Balance, two pairs of Italian-made Oliver Cabells, a cheap pair of white Adidas Stan Smiths, and some Asics that I promptly returned. Incidentally, one pair of the Oliver Cabell shoes are all but unwearable, causing oozing blisters at each step. And it’s too late to return them. My Visa is writhing.

The indulgence is appalling. I’m no sneaker-head. I don’t collect footwear. I am not Imelda Marcos. I just need a fresh fleet of shoes to replenish the worn and rejected. If the latest New Balance are good, I will return the Cole Haans. That will mean I will own only five new pairs of sneakers. One of those causes blisters. So that means four new pairs. Not so dramatic after all. But still: really?

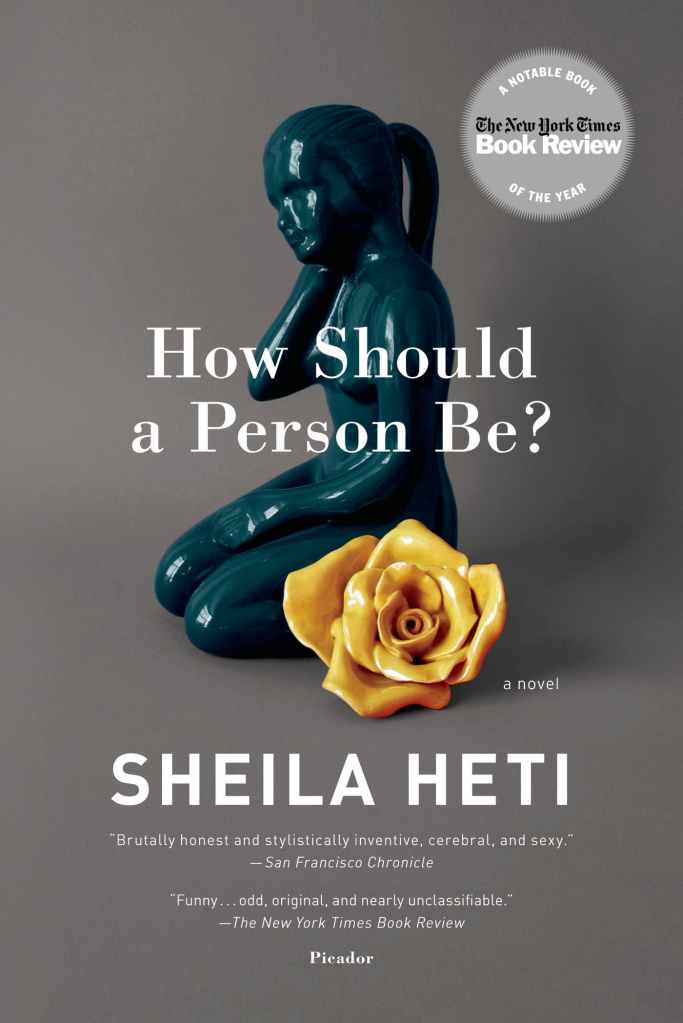

4. Next to Michael Mann’s cop thriller “Heat 2,” a brilliant, blistering, book-form sequel to his 1995 crime movie masterpiece “Heat,” with Robert De Niro and Al Pacino among other badasses, the best book I read this summer was Sheila Heti’s “How Should a Person Be?” — sticky auto-fiction that giddily pinballs through its meandering idiosyncrasies. This jagged, brainy book functions with the itchy buzz of life. It’s hilarious. Awkward. Wincing. Wonderful. Yeah, life.

Narrated by a 30-ish Heti, it’s aptly described as “part literary novel, part self-help manual, and part vivid exploration of the artistic and sexual impulse.” It happily recalls the sui generis first-person fictions of Rachel Cusk, Jenny Offill and Elif Batuman, currently my favorite writers. They kind of drop you mid-thought into their lives, then roll on from there with chatty, funny, unembarrassed realism. The works revel in their mundanity, which becomes a kind of magnificence.

Heti’s 2012 novel was named one of 15 “remarkable books by women that are shaping the way we read and write in the 21st century” by The New York Times. A bold but clear choice I wholly endorse. Heti has a new novel, “Pure Colour,” that I wasn’t bonkers about, but you might find worth a peek. For now, “How Should a Person Be?” is what I’m bellowing about from the mountaintop. (Me. Megaphone. A towering crag.)

5. If you want to know something about me, read this tart and telling passage from Elizabeth McCracken’s new novel “The Hero of This Book”:

“Myself, I loathe having my picture taken. I have for as long as I can remember, even in the old days when you could go weeks without somebody trying. In all group shots I am not pictured. It’s beyond vanity and in the realm of superstition. I don’t like people looking at me. I don’t like being the center of attention except under very specific conditions. … I will not stop for a photo. I will not look at myself in a mirror for you. I will not watch myself pass in a plane-glass window.”

There. Now you know a bit more about me. Also, I’m not big on dragons.