A slight, gaunt man, with a mummy’s sunken eyes, Harry Dean Stanton seemed eternally haggard and, in his later days, alarmingly cadaverous. He finally gave way to his looks: Stanton, a reticent, lived-in character actor with a gentle heart beating beneath a leather exterior, died yesterday. He was 91.

Stanton’s best-known work includes “Paris, Texas,” “Wise Blood,” “Repo Man,” “The Rose,” “Pretty in Pink” and HBO’s “Big Love.” I don’t have much to say about his passing, except that it’s sad and that I have potent memories of his performances, especially his role as doomed Brett in 1979’s unshakable “Alien.” Even then he had a Keith Richards mien going on.

I met Stanton briefly in 2003 at a club concert in Austin, Texas, that Stanton, in town shooting a film, reluctantly attended. This is what I blogged then about the special, if tentative, encounter:

One night at Antone’s nightclub, actress Gina Gershon was rocking and Harry Dean Stanton was frowning. “It’s loud, strident and violent,” Stanton said of the three-chord crunch Gershon and her backup group Girls Against Boys were discharging like the solid bar band they were pretending to be. “It’s an assault on the senses.” (It’s rock ‘n’ roll, Harry.)

Hanging out alone at the end of the bar next to the candy machines, Stanton appeared slightly forlorn during the show, nursing what looked like a whisky sour but might have been ginger ale, skittishly glancing around, producing sweet but wavering smiles when approached by pretty women who would wrap an arm around the black blazer that hung on his slight frame with a vaudevillian droop.

Gershon was on a short club tour, living out her long-held musician’s fantasy, putting down the air-guitar for a Gibson SG. She drew about 400 people to Antone’s, about half appearing to be guest-list rubber-neckers. Including Stanton.

Stanton, 77, has 100 films to his credit, some of the best being “Cool Hand Luke,” “Paris, Texas” and “Alien.” He was in Austin shooting the Luke Wilson-directed “Wendell Baker Story” and has been spotted at unlikely places like Club Deville, where friends tell me Luke and Owen Wilson enjoy tearing it up. Not sure why Stanton was here, but his “Baker” co-star Seymour Cassel dropped in late during the show, said something to Stanton and waded into the crowd of mostly thirtysomethings.

As the show wound down with a tight cover of The Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog,” my girlfriend offered Stanton some Reese’s Pieces bought for a quarter from one of the candy machines. He looked into her open palm and asked, “What are those — M&M’s?” He puzzled over the morsels as if studying Martian soil. Then a trio of pretty girls enfolded him in their attentions, and he was gone.

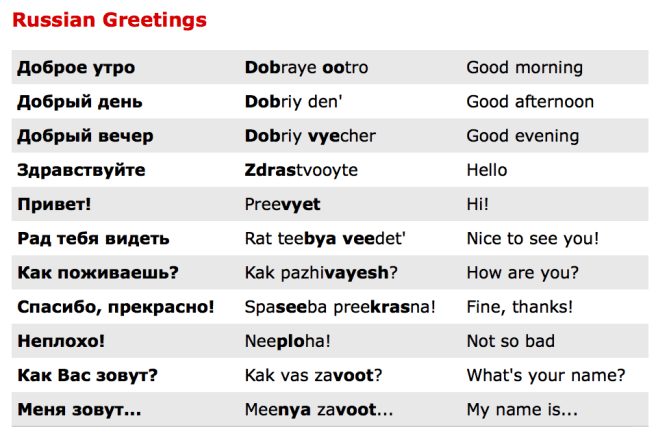

Call me a language wuss. I’m over it. I bone up, some, and I always do fine. I’m obviously not a big talker abroad, unless my interlocutor speaks English, then we have a fine old time. Russia just seems different. I’ve read repeatedly that you’ll have the best luck with English-speakers among millennials, students and the like, which makes sense. That’s how it was in Japan and China. Young people are learning the language and they absolutely love to practice with native speakers. I’ll be avoiding all locals with wrinkles, paunches and tweed berets.

Call me a language wuss. I’m over it. I bone up, some, and I always do fine. I’m obviously not a big talker abroad, unless my interlocutor speaks English, then we have a fine old time. Russia just seems different. I’ve read repeatedly that you’ll have the best luck with English-speakers among millennials, students and the like, which makes sense. That’s how it was in Japan and China. Young people are learning the language and they absolutely love to practice with native speakers. I’ll be avoiding all locals with wrinkles, paunches and tweed berets.

Done correctly, writing is work, grueling toil. It’s fun (when it’s going well), but not that much fun. Still, creating and thinking are so gratifying that it’s worth it. It takes time, hours and hours. Listen to Louis Menand of The New Yorker:

Done correctly, writing is work, grueling toil. It’s fun (when it’s going well), but not that much fun. Still, creating and thinking are so gratifying that it’s worth it. It takes time, hours and hours. Listen to Louis Menand of The New Yorker: